Interns at Real Food Farm — Hard Work, Pride, and Good Food

“Hard work. Hot. And what can I really even learn out of it?”

Those were Davon Baynes’s thoughts when he started as an intern at Civic Works’ Real Food Farm in Baltimore’s Clifton Park. He wasn’t the only intern who felt that way. In fact, all six students who participated in the program that year said they learned that growing food is hard work. Davon, a high school junior when he began, wasn’t turned off from farming, though; he went on to become the assistant manager of the Mobile Farmers Market and now spends his days harvesting and selling Real Food Farm produce in his community.

So, how do you get teenagers interested in working on a farm? Especially on precious Saturday mornings? That was one of the big questions that the new farm Education Coordinator wanted to answer when she was revamping the internship program in Spring 2012. With funding from a CLF Carl Taylor student research grant, I worked with her to try to answer that question from the interns’ points of view. I wanted to find out what promoted their engagement in the program and how they were personally benefiting. A lot of it came down to the satisfaction of having a paid job and growing their own food.

Through in-person interviews, the six students who participated in the program in 2012 and 2013 told me repeatedly how hard it was for high schoolers to find jobs here in Baltimore, and they spoke with pride about being able to earn their own money. But they also said that the financial motivation alone wasn’t enough—you had to be up for a challenge if you were going to stick with it through the heat and cold. Although the physically demanding work took some getting used to, they all agreed that growing their own food was what made the effort worthwhile. That year, each intern had a personal plot inside a hoophouse where they could plant whatever combination of vegetables that they wanted. They were responsible for tending their plots each time they came to the farm. They proudly showed me beds full of carrots, spinach, lettuce, and other greens, and talked about taking veggies home to eat with their families. That took some getting used to as well. As Davon explained, “For the food on the farm, when you eat it raw, it just don’t feel right. Until you keep doing it. And then you like, oh, that’s how real food supposed to taste. I would say [it takes] at least a month. Yeah, at least a month. Then I started growing my own plot. And I had to think ‘Oh, I gotta eat this food once I grow it.’ Yeah, then you start liking it.”

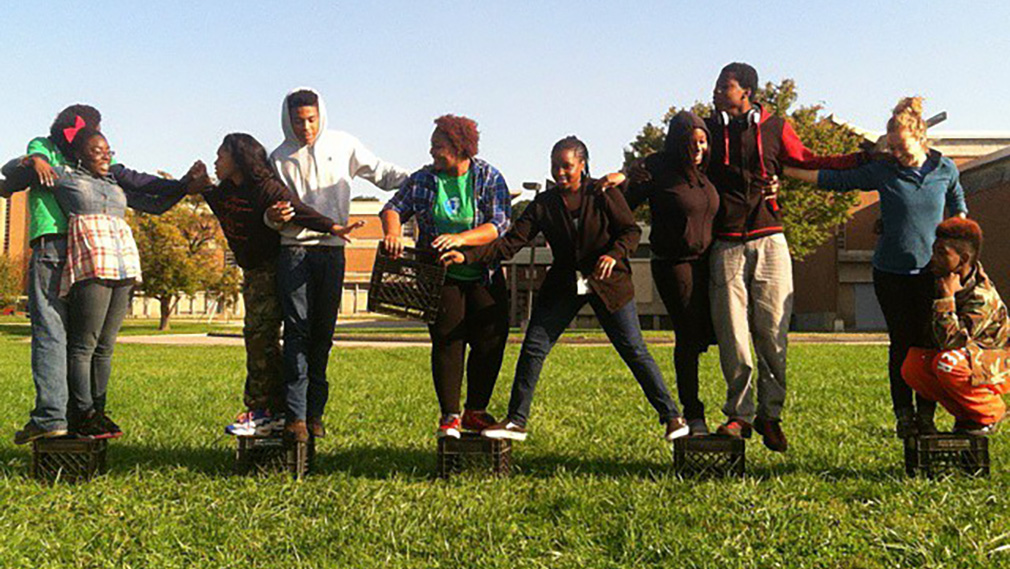

The Real Food Farm internship program continues to cultivate leaders and healthy eaters and has graduated 15 alumni, some of whom, like Davon, continued to work with the farm and Civic Works after the internship ended. This school year, ten high school interns have engaged in workshops on cooking, farming, leadership, service, and food justice. The results are tangible and extend beyond the farm and kitchen; this year’s crew has reported not only better eating habits but more comfort with public speaking and an elevated sense of how they can make a difference in their community. Real Food Farm will also employ more than 35 students this summer in partnership with Baltimore City’s YouthWorks program. Real Food Farm is in good company; youth agriculture programs continue to sprout up across the United States, spreading food justice and youth empowerment to the communities they serve.

Many thanks to the current Real Food Farm Education Coordinator Molly McCullaugh, and the previous Education Coordinator Liana Przygocki, for their collaboration on this research project and contribution to this blog post! Here’s more information about the CLF’s Carl Taylor recipients and about Elena’s CLF-Lerner Fellowship.