Women, the World Wars and the Meatless Campaigns

Meatless Mondays aren’t new. Nor is eating less wheat, raising chickens, or planting backyard vegetable gardens.

One hundred years ago, on the World War I home front, the fork became a rifle and the kitchen a trench. “Every gardener in the land has a part to take in the fight! His duty awaits him just as certainly, and, if anything, more imperatively, in the rows of vegetables in his garden, as does that of the soldier in the trenches at the front,” proclaimed the Wisconsin’s Sheboygan Press in 1918. “The gardener who does not plan his garden well, who fails to plant the right kinds of vegetables, who neglects his garden after it is planted, is a Slacker.”

Eating more vegetables and less meat became patriotic during the war. Everyone was urged to do his or her part. Millions of Americans joined in, waving spinach along with their flags. No one wanted to be a slacker. And Wisconsin helped lead the way.

The outbreak of war brought tremendous shortages of food across Europe. By the time the United States entered the war in 1917, three years of fighting had seriously damaged European production. U.S. entry into the war only further disrupted the supply of food.

As an agricultural state, Wisconsin took a keen interest in the food crisis. Wisconsin quickly formed a State Council of Defense to implement, supervise, and regulate war activities, the first such organization in the nation. Its chair, Magnus Swenson of Madison, began promoting food conservation before Congress had even created the United States Food Administration to do the same nationally.

Swenson was the perfect person for the job. He’d spent his career studying industrial efficiency.

In Wisconsin, Swenson attacked food hoarding, urged citizens to cultivate backyard vegetable gardens, and instituted the centerpiece of his plan, “meatless” and “wheatless” days.

When President Woodrow Wilson put Herbert Hoover in charge of the newly created the Food Administration, Hoover was so impressed with Swenson and Wisconsin’s efforts that he adopted many of Swenson’s policies. He also took to Swenson’s model of making women, gardens, and kitchens the first line of defense on the home front.

Women joined the war effort without ever leaving the kitchen. Meatless and wheatless days became the centerpiece of Swenson’s home food plan. Soon, the whole country joined in.

Swenson recognized the vital role that women played in family meals and purchasing decisions. He, along with home economists, university extension agents, and leaders in local councils of defense, urged women to use their power patriotically by refraining from using certain foods. In the kitchen, women learned to use corn and rye instead of wheat, chicken instead of beef, and to cook more vegetables. In Wisconsin, Mondays and Wednesdays became wheatless days and Tuesdays became meatless, adopted in homes as well as in restaurants in university cafeterias.

Before radio and television, conservation messages reached women through newspaper articles, window displays, word-of-mouth, and personal visits from home economists. Home economists wrote articles and published free guides to using less meat, wheat, fat, and sugar.

The University of Wisconsin’s Women Students’ War Work Council and the Home Economics Department produced a wartime recipe booklet to show how easy it could be to cook with alternative ingredients. Recipes included steamed barley pudding, scalloped cheese, liver pudding, and something called “salmon box”—a loaf pan lined with rice and filled with cold, flaked salmon.

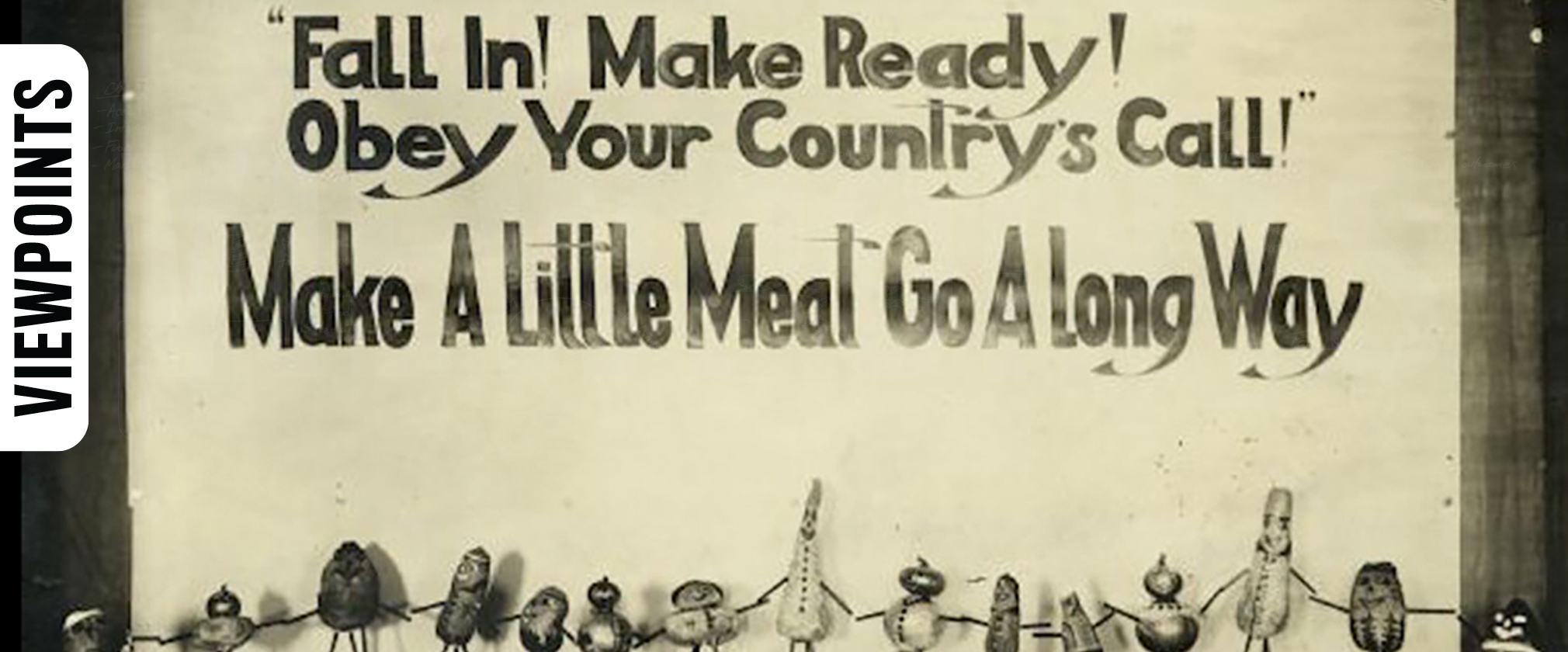

In towns and cities, women’s committees and clubs created window displays to advertise and educate consumers on food conservation. Many of these weren’t just simple cardboard displays, though.

In Madison, Wisconsin, the Woman’s Committee of the Dane County Council of Defense hired architects from the University of Wisconsin to help craft displays for windows in grocery, department, and other stores. One had a Mother Goose theme and featured nursery rhyme style verses: “Mistress Mary – Quite contrary/Wants beef and mutton too?/Why! All I’ve got is halibut/And chicken for the stew.”

Hundreds of women eagerly joined committees of the State Council of Defense to help devise, teach, and implement food conservation programs. Councils organized lectures and demonstrations on food preservation methods. The University of Wisconsin’s College of Agriculture and the home economists from the University of Wisconsin Extension invited women to attend free conservation classes in communities around the state.

Even children took part. In schools, kids found posters proclaiming the value of corn and potatoes. Their teachers read them books like the Fairy Story on Potatoes to encourage more meatless and wheatless meals.

No one had to do any of these things: all were voluntary. Yet thousands of thousands of women signed pledges promising to reduce waste and conserve much needed war foods. More than 80 percent of the women in Milwaukee County signed on, and over 10 million American women eventually signed the pledge.

At the end of the war in 1918, billions of pounds of meats, fats, dairy, and sugar had been shipped to the Allies. President Wilson sent Hoover to Europe to lead a new food organization, the American Relief Administration, to help countries devastated by war. With him was Wisconsin’s Magnus Swenson, who brought his experience in Wisconsin to the postwar crisis.

And two decades later, the conservation model developed in Wisconsin and adopted nationally during the First World War guided efforts during the Second World War.

Erika Janik is a writer, historian, and the executive producer of Wisconsin Life on Wisconsin Public Radio. She's the author of six books and dozens of articles on women, food, and history. erikajanik.com

Images: “Fall In! Make Ready!” Wisconsin Historical Society.