Time to Put Community Food Projects Back on Track

SANTA FE, N.M.—December 14, 2021. In spite of a large (but often struggling) agriculture sector, the state of New Mexico has endured some of the worst food insecurity rates in the United States. For years, anti-poverty advocates kept hunger at bay with food banks and food stamps (now known as SNAP), while small farmer activists fought for higher farm prices by organizing farmers markets.

But as the 20th century drew to a close, the state’s food system stakeholders began asking themselves if there might be a better way. Could they benefit lower-income households at the same time they helped farmers? Going further, could they possibly find a common cause with government agencies around a shared vision for a just and sustainable food system?

They found their answers in the relatively new USDA Community Food Projects Competitive Grant Program (CFP). According to Pam Roy, executive director of the New Mexico-based non-profit Farm to Table, “CFP became the launching pad for all our community food initiatives. With a three-year, $300,000 CFP grant in 2001, we planted the food system seed, and it’s never stopped growing!” During that time, the grant enabled Farm to Table to start a new farmers market that served Santa Fe’s low- and middle-income communities, develop the state’s first farm-to-school program, and create the New Mexico Food and Agriculture Policy Council.

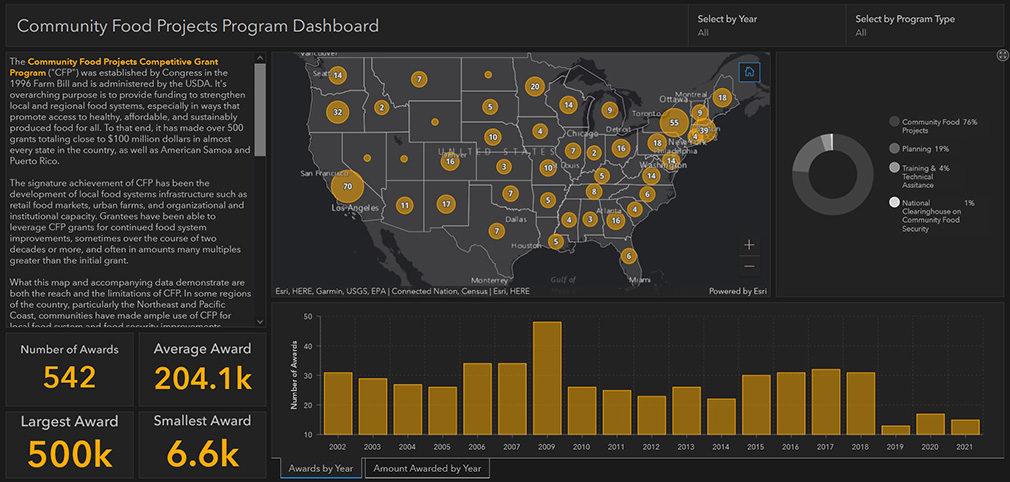

CFP celebrated its 25th anniversary in 2021. Authorized by Congress as part of the Federal Agriculture Improvement and Reform Act of 1996 (more commonly known as the farm bill), the program has awarded about 650 grants worth nearly $100 million to hundreds of communities in almost every state and US territory. (More information about the distribution of CFP grants from 2002 to 2021 can be found at Community Food Projects Program Dashboard). The program’s Congressional language clearly set it apart from previous federal food and farm initiatives by stating that funded projects will “meet the food needs of low-income people…increase the self-reliance of communities…promote comprehensive responses to food, farm, and nutrition issues.”

Looking ahead, the lessons learned and impacts achieved strongly suggest that CFP should not only be reauthorized in the next farm bill, but at a funding level considerably higher than its current $5 million per year.

No one can attest to CFP’s significance better than Dr. Elizabeth “Liz” Tuckermanty. As USDA’s National Program Leader for CFP from its inception to her retirement in 2012, Liz developed much of the superstructure and nuance that gave the program its most distinguished features.

She told me that when she first took the position, she thought, “Now we can finally talk about food systems because every time I had brought up the subject in USDA, I would get pushback.” She also emphasized that the program “was innovative; grants could run for three years (now four), and funded projects were required to have multiple partners. This gave communities a chance to look at a much longer horizon, and even dream a little.”

As Liz Tuckermanty saw it, CFP enabled grassroots groups to develop food projects for the first time. In close collaboration with the emerging network of community food system stakeholders, she carved out small pots of money for training and technical assistance. These additional resources nurtured a culture of mutual support between new and “veteran” community food security and justice organizations that strengthened everybody’s work. In 2002, with the advent of one-year, $35,000 planning grants, CFP enabled even more “first-timers” to prepare projects that might become eligible for the maximum $300,000 (later to become $400,000) grants.

Through growth in their confidence and competence, Farm to Table and their partners leveraged their CFP grant to the hilt. Over the past 20 years, they secured tens of millions of dollars from the New Mexico state legislature and other sources to support farm-to-school and farm-to-senior meal initiatives, “Double-up Bucks” programs for SNAP recipients at farmers markets, and local produce incentive programs for the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children (WIC). Summing up two decades of progress, Pam Roy said, “CFP’s multiplier effect has been massive!”

The good news is that it no longer takes 20 years to have a substantial impact on a community’s food system. In Bridgeport, Connecticut, Green Village Initiative (GVI), a 2018 CFP grant recipient, has turned vacant urban lots in this struggling post-industrial city into 12 community gardens including a two-acre urban farm. Seven farmers markets are also bring fresh, local food to the city’s low-access food areas, while Black-owned, private urban farms collaborate with GVI to operate Connecticut’s only all-Bridgeport grown farmers market.

To fill another urban community with good food and to provide incubator space for BIPOC-owned food businesses, the Lexington, Kentucky, North Limestone Development Corporation (NoLi) developed the Julietta Public Market. Housed in a beautifully remodeled interior space of a former bus garage, 90 food vendors, most of them minority and start-up, sell their wares. One of the anchor vendors is Black Soil, an organization dedicated to assisting Kentucky’s Black farmers. In addition to operating several market stalls that only sell Kentucky-grown produce, Black Soil provides an array of educational, outreach, and aggregating services to the state’s Black farmers.

A 2020 CFP grant is supporting the development of this neighborhood economic development engine. According to Lexington City Councilman James Brown, “Julietta Market is filling the food gap with lots of healthy food and educational opportunities. The Market is heaven sent, and the Community Food Projects grant made it happen!”

While CFP has spawned hundreds of similar community food stories across the country, it doesn’t come without flaws. Federal grant administrative requirements have been so onerous as to deter many smaller, lower capacity organizations from applying. As Eleanor Angerame of GVI told me, she almost didn’t accept the executive director job offer made to her when she discovered how difficult CFP’s administrative requirements were. The loss of a CFP grant would have been a serious blow to resource-thin Bridgeport.

Writing CFP grants require skill and lots of time, as well as a Congressionally mandated dollar-for-dollar match. Various disruptions at USDA since Liz Tuckermanty’s departure have also led to a decline in training and technical assistance. All of this has contributed to an inequitable distribution of CFP funds. As the CFP grant distribution dashboard makes clear, less than 10 percent of grants went to the 13 southern states, which have 36 percent of the country’s population, and most importantly, higher rates of poverty, food insecurity, obesity, and diabetes.

To correct these problems, USDA must:

- Reinvigorate CFP’s training and technical assistance services

- Reduce the match to one dollar in non-federal support for every two dollars of federal funds

- Set aside funding for states and regions with the greatest food security needs and lowest resource capabilities

- And, based on the number of high-quality CFP applications received every year, increase annual funding to $15 million.

When Congress established CFP 25 years ago, former Texas Congressman Eligio “Kika” de la Garza referred to it as “…a comprehensive strategy…that incorporates the participation of the community and encourages a greater role for the entire food system.” Letting people determine their community’s needs and devise their own solutions is what CFP has been doing since its inception. It’s time to make those strengths and achievements more prevalent.