A Red State Rejects the Right to Farm

Something interesting happened in Oklahoma. On November 8, this state, typically associated with a rural, farming and ranching way of life, did as expected: the majority of Oklahomans (65 percent) voted for the Republican presidential candidate and all seven of the state’s electoral votes went red. But something a little unusual happened, too. That same day, 60 percent of Oklahoma voters opposed an amendment typically associated with the Republican agenda—the so-called “right to farm.” In essence, Oklahoma elected a right-wing presidential candidate who has promised to do away with environmental regulations, while simultaneously voting to uphold current regulations on farming and ranching.

What the what?

The Oklahoma Stewardship Council is a broad coalition that was organized to fight the “Right to Farm” bill, State Question 777, which some called the “Right to Harm” bill. I spoke with Cynthia Archiniaco, the Council’s treasurer, and she said, “We were blown away by the results. We were just in shock.”

The intended goal of SQ 777 was to allow farmers to insist that courts rule on laws they deem too restrictive. So, for example, if 777 had passed, a farmer or rancher would be able to take to court any regulation that he or she felt impinged too much on the business—and the court would be required to give the law strict scrutiny. SQ 777 would have been retroactive, lassoing in laws from two years ago, and most likely applying to regulations aimed at conservation, food safety, water quality, and animal welfare.

Two days after the election, a fourth-generation farmer was quoted in The Oklahoman: “… he believes urban voters did not fully understand the issue. He and other farmers who supported the measure fear animal welfare and environmental groups will push legislation in the state regulating everything from the size of chicken cages to methane emissions from cows.” He went on to say that urban consumers are “totally disconnected from what and where and how their food is produced.”

Indeed, there was an east-west, rural-urban split. The western counties, where most of the state’s farming and ranching occurs, voted in favor of 777, whereas the eastern counties, which include Tulsa and Oklahoma City, voted against the measure. The Farm Bureau supported SQ 777 and accused the opposition of fear-mongering.

So how was the opposition able to win? Each side of the question raised and spent about the same amount of money on advertising by radio, television and billboard. Archiniaco credits the win with the broad coalition from a vast array of allies, each free to promote their own message. “It was a dozen tiny stings all over the head and body,” she said.

One of the big supporters of the Vote No campaign was the Humane Society, but Archiniaco said that they downplayed the animal welfare angle because people don’t like to feel pressured into becoming vegetarians. “We said this wasn’t about passing feel-good legislation, but it was about common sense—you eat what the birds eat, so do you really want to be pumping them full of all this stuff [antibiotics] because they’re in cramped quarters?”

The campaign emphasized family farmers above all: their voices, their votes, their concerns. The campaign emphasized standing up to corporate interests and ensuring that Oklahomans have a “fair say.” The Vote No boogeyman was Big Ag.

It worked. An Oklahoma City councilman is quoted as saying that SQ 777 was a play to allow big corporations to not have to follow regulations. Tulsa voters heard about how their taxes would go up if 777 passed, because they’d have to pay more to filter drinking water that would become more polluted as regulations were eased. Some opponents invoked the specter of cockfighting and puppy mills.

The Vote No campaign got support from many animal welfare and environmental organizations , as well as from all the living former Oklahoma governors, the Inter-Tribal Council of the Five Civilized Tribes, and some fishing organizations.

“The broad focus worked well,” said Archiniaco. “But we know they’ll try again next year.”

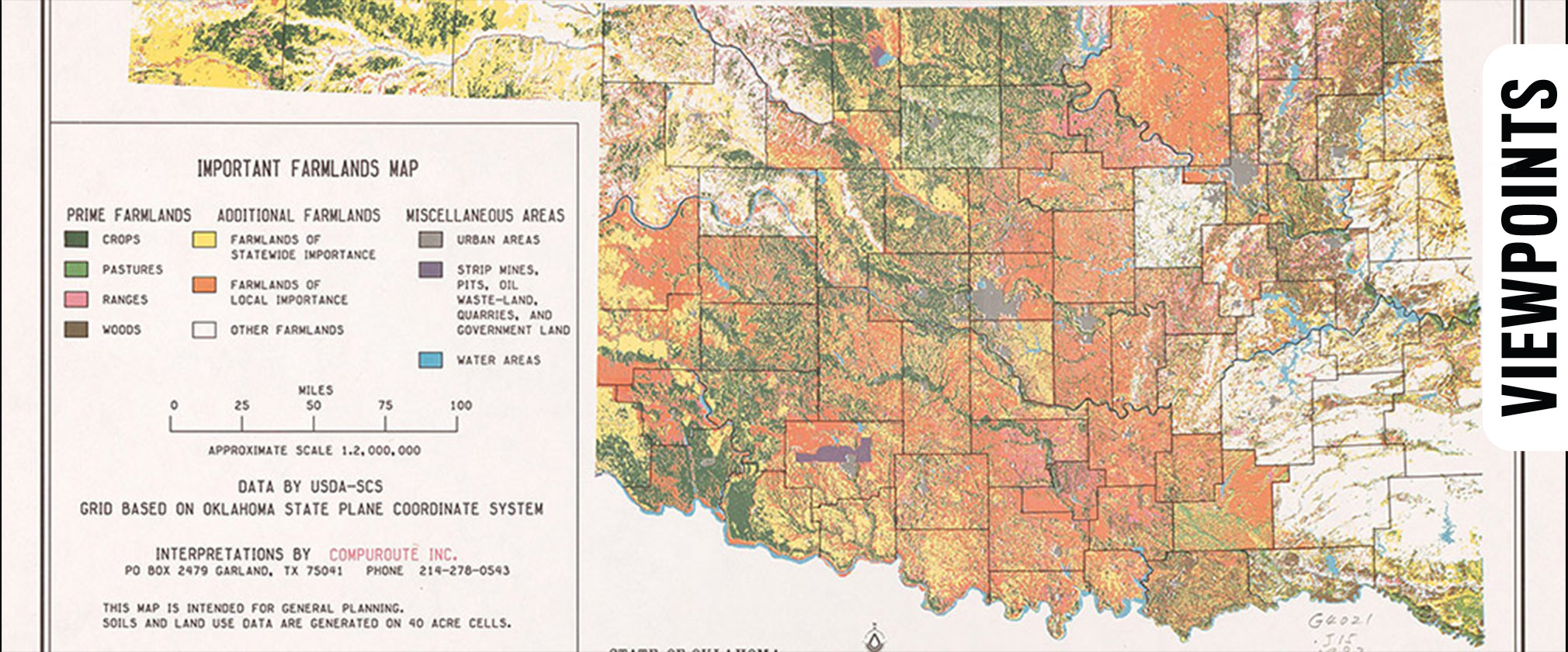

Image: From Wikimedia Commons