Poultry Contracting and Tournament Pricing

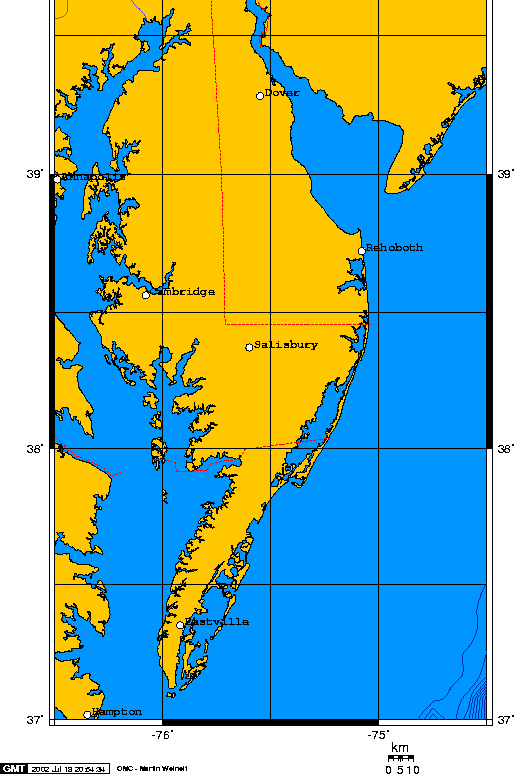

The Johns Hopkins Center for a Livable Future was one of the sponsors of the recent Annapolis Summit 2015 organized and conducted by The Daily Record and The Mark Steiner Show on WEAA-FM. I attended the summit, and asked Maryland Attorney General Brian Frosh a question about poultry contracting and the tournament pricing system (which I’ll explain later) that is common in the poultry industry on the Delmarva Peninsula.

The Johns Hopkins Center for a Livable Future was one of the sponsors of the recent Annapolis Summit 2015 organized and conducted by The Daily Record and The Mark Steiner Show on WEAA-FM. I attended the summit, and asked Maryland Attorney General Brian Frosh a question about poultry contracting and the tournament pricing system (which I’ll explain later) that is common in the poultry industry on the Delmarva Peninsula.

The number of broilers produced in the United States has increased 1,400 percent since 1950, while the number of poultry growing-operations has declined by 98 percent [1]. Approximately 525 million broilers are raised annually on the Eastern Shore alone, which is nearly 6 percent of the nation’s production on .05 percent of U.S. landmass. Those birds produce 42 million cubic feet of waste a year, enough to fill the dome of the U.S. Capitol Building weekly. [2]

The high number of animals concentrated in such a small geographic area represents a threat to public health due to the industry’s standard production protocols and the over-application of chicken waste, which degrades the environment. The best solution to this problem would be to reduce animal density and reincorporate animals into a crop rotation system.

The current system is built on the contract production relationship between the producer (farmer) and the large integrator (company). Those contracts make the disposal of waste and dead birds the sole responsibility of the producer. In addition, requirements for feeding and care of the birds, time of delivery and pick-up for slaughter are all dictated by the company. The only aspects of the common poultry contract relationship controlled by the farmer are debt, dead birds, and waste. An additional prop supporting the industrial poultry production system is the tournament pricing system, which companies use to determine what will be paid to farmers.

The tournament pricing system was designed by the major poultry processing companies to control producers by pitting farmers in a region against one another. The best description of the contract relationship and tournament pricing system is outlined by Christopher Leonard in his 2014 book, The Meat Racket: The Secret Takeover of America’s Food Business.

“Tyson also sets the prices for it birds. When the chickens arrive at the slaughterhouse, Tyson weighs them and tallies up how much it owes the farmer on a per-pound basis. When that price is determined, Tyson subtracts the value of the feed it delivered to grow the birds. This determines a rough payment for the farmer. But the farmer isn’t paid this flat fee. Instead, final payment is based on a ranking system, which farmers call the “tournament”. Tyson compares how well each farmer was able to fatten the chickens, compared to his neighbors who also delivered chickens that week.

The terms and conditions of Tyson’s relationship with its farmers are laid out in a contract the farmer signs with Tyson. This contract is the single most important document for a farmer’s livelihood. It ensures the steady flow of birds a farmer needs to pay off utility bills and bank debt. But for all their importance, the contracts are usually short and simple documents. While a farmer’s debt is measured in decades, the contracts are often viable for a matter of weeks and signed on a flock-to-flock basis. Farmers certainly have the right to negotiate terms when the contract is laid out on the hood of a Tyson truck that has arrived to deliver birds, but most often they do not. They accept the terms and sign. The contracts reserve Tyson’s right to cancel the arrangement at any time.” [3]

The contract and tournament system outlined in Leonard’s book has become the model used industry-wide, including by Perdue and Mount Aire. There is no price or contract transparency and integrators use the tournament system to turn producers against one another. It is common for producers performing in the lower half of tournament to lose their contracts after three or four consecutive low rankings.

At the Annapolis Summit, I asked that the Attorney General lead an effort by the Attorneys General of the three states on the Delmarva Peninsula (Delaware, Maryland, and Virginia) to investigate the contract and tournament pricing system. And since New York and Pennsylvania are part of the Chesapeake Bay watershed, it would make sense to include those states as well.

A similar effort was led by Iowa Attorney General Tom Miller in the mid 1990s in an effort to stem the tide of the growing influence of large hog companies in Iowa hog production. He initiated a multi-state effort in Midwestern and Great Plains states to ban corporate ownership of hog operations through legislation in each state, as had been done in Iowa. One of the large swine companies, Smithfield, challenged Iowa’s ban in court and, as a result, Attorney General Miller negotiated a settlement with Smithfield to require contract transparency, price reporting, and the protection of hog farmers’ rights to assemble and openly discuss contract issues.

Poultry producers should not lose their rights to freedom of association and free speech just to maintain their business relationship with a poultry company. Poultry companies need to address animal density issues, and share in legal and financial responsibility for proper waste management with their contract producers. Furthermore, state monitoring and regulation of waste transported off these concentrated animal feeding operations is essential. Maryland taxpayers do have a stake in this fight. Millions of taxpayers’ dollars help defray the cost of waste storage, as well as funding transportation of waste off of the peninsula, not to mention support for Chesapeake Bay clean up costs.

[1] The Pew Charitable Trust. July, 2011. Big Chicken: Pollution and Industrial Poultry Production in America, Retrieved from http://www.pewtrusts.org/~/media/legacy/uploadedfiles/peg/publications/report/PEGBigChickenJuly2011pdf.

[2] Ibid

[3] Leonard, Christopher. The Meat Racket: The Secret Takeover of America’s Food Business. Simon and Schuster, 2014.

Image: “Delmarva” by Planiglobe – Mercator projection: Online Map Creation. Licensed under CC BY 2.5 via Wikimedia Commons