Climate Action, Food Systems and Undernutrition

The world is beginning to understand that our food systems play a role in climate change—and that by improving our food systems now we might be able to mitigate some of the more devastating shifts in climate yet to come. With more than 20 years of experience investigating the negative consequences of our food systems, especially industrial food animal production, the Center for a Livable Future has gained tremendous insight into the associated externalities of the predominant model, one of which is climate change. Other externalities we’ve focused on include antibiotic resistance and environmental degradation, to name a couple.

Across the board, I’ve noticed expanded interest in the connections between food systems and climate action, from the United Nations to nonprofit sustainability organizations to chefs to research institutions to Google to the Prince of Wales. So finally, the interest and will to make positive change is there, from a wide group of stakeholders. But I fear we don’t have much time. We must get our act together and be bold—but I cannot emphasize enough how important it is to do this in a way that’s not only practical, but fair.

Background: Sustainable Development Goals and UNAIDS

Unlike the Millennium Development Goals, which were designed and implemented for low- and middle-income countries, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are for all of us. Climate change can’t be handled by only a subset of countries, and we have to erase our traditional notions of domestic versus international work. Wherever we work, we are part of the world, and all our actions in the field of food systems are interlinked.

The SDGs can be defined as wicked problems, and wicked problems cannot be solved with a single solution. We can learn a great lesson about solving wicked problems by looking at the field of HIV/AIDS in the past 50 years under the leadership of UNAIDS.

The UNAIDS Joint Program is the only UN program in which all stakeholders had and have their role, and most importantly, people living with HIV were at the core of the program. In the early 1980s we couldn’t even define the disease, but now in 2018 with the help of the private sector we can test and treat PLHIV almost immediately. Human rights are at the heart, and the joint program learned that it had to re-think its language in order to be truly inclusive. For example, terms such as “prostitute,” “HIV patient” and “drug addict” had to be replaced with more sensitive language. The result was: “sex worker,” “people living with HIV” and “drug user.”

In our food systems and climate change work, do we use terms that exclude certain groups?

Another extremely important lesson from the UNAIDS joint program is that it moved ahead using incomplete information, while simultaneously continuing to conduct essential research to fill the knowledge gaps in various fields. Compared to the body of knowledge we had about HIV back then, we have more knowledge now about the issues in the food system—and we need to take action now. The framework developed by Institute of Medicine in 2015 (Essential Readings, below) is a great tool to develop strategies along the value chain with the following perspectives: markets, policies, biophysical environment, science and technology, and social organization.

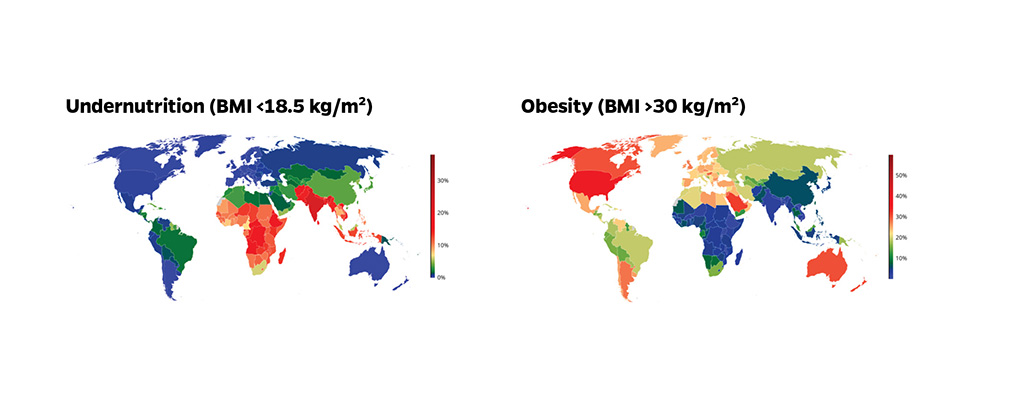

Obesity in the Global North, Undernutrition in the Global South

The global nutrition report showed that the world has to cope with all forms of malnutrition: hunger (calories), undernutrition (wasting and stunting), overnutrition (overweight/obesity), and micronutrient deficiencies. Although we have seen a reduction in hunger and undernutrition in low- and middle-income countries, or LMICs, the trend in overnutrition and obesity is alarming. In 2013, Ruel and Alderman showed that an increase of 10 percent of gross domestic product correlated with a decrease of 6 percent in stunting and increase of 7 percent in maternal obesity. It is clear that economic growth is a strong driver behind the shift in types of malnutrition in many LMICs. The poor spend a large percentage (up to 70 percent) of their income on food, and their diet consists mainly of staple foods such as rice, maize or corn, or wheat, which are low in essential amino acids and micronutrients. These plant-based diets are not the same nutrient-adequate, plant-rich diets consumed by adult vegans or vegetarians in the US or Europe. These diets, comprising mainly staple foods, are determined by poverty and lack many of the essential nutrients.

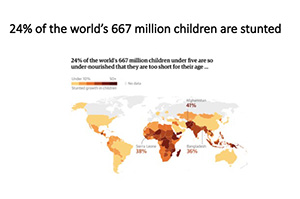

Since the first Lancet nutrition series came out in 2008 under the leadership of Robert Black, here at Johns Hopkins, we understand much more about the etiology and the consequences of stunting. Stunted children have higher mortality risk and a lower cognitive development. The effects of stunting are irreversible at the age of two, and stunted children are at risk of obesity and cardiovascular diseases later in life. Furthermore, stunting also has negative economic consequences on children affected at the age of two. The long-term impact of stunting in LMICs is substantial—and the impact is long-ranging, lasting entire lifetimes.

Since the first Lancet nutrition series came out in 2008 under the leadership of Robert Black, here at Johns Hopkins, we understand much more about the etiology and the consequences of stunting. Stunted children have higher mortality risk and a lower cognitive development. The effects of stunting are irreversible at the age of two, and stunted children are at risk of obesity and cardiovascular diseases later in life. Furthermore, stunting also has negative economic consequences on children affected at the age of two. The long-term impact of stunting in LMICs is substantial—and the impact is long-ranging, lasting entire lifetimes.

But another important note about undernutrition is that it often leads to obesity later in life. So when we look at the obesity epidemic, we need to keep in mind that some of that is a result of undernutrition early in life. Earlier this year, a Lancet Commission published a report— The Global Syndemic of Obesity, Undernutrition and Climate Change—that reinforced again that attacking stunting in LMICs is the first step in the fight against obesity.

When I was in Bangladesh in 1989, 30 years ago, 70 percent of the children suffered stunting. The effects of that are still very much with us today, as those children grew up and now 70 percent of Bangladeshis in their early 30s are at risk of chronic heart diseases, lower cognitive development and obesity because of malnutrition when they were infants. Twenty years from now, when those children are in their early 50s, that impact of stunting will still be with us, as those adults will still be affected by the same risks associated with stunting. It is mindboggling. The global nutrition report showed that we currently have 155 million stunted children, but if you factor in how the negative effects of stunting last entire lifetimes, until the stunted infant dies as an adult, billions of people are affected by the long-term epigenetic consequences of stunting. Over 30 percent of the Chinese in their 30s are affected by childhood stunting, despite the fact the current prevalence is less than 10 percent—and this 30 percent will continue to be adversely affected for their entire lifetimes. As I mentioned previously, stunting prevention does not only lead to optimal cognitive and other forms of epigenetic development but also reduces the risk of obesity and chronic diseases in most LMICs.

A good understanding of how poverty leads to stunting and eventually to obesity is very important. The poor will improve the nutrient content of their diet as their access to more nutritious and animal-sourced foods increases as a result of GDP growth. A recent study by CLF showed that most of the LMICs don’t produce enough of the right food to feed their citizens a nutrient-adequate diet. Many studies in the past decades showed that micronutrient deficiencies remain highly prevalent in LMICs. The World Food Program’s “fill the nutrient gap” research confirmed that the poor cannot afford or buy a local diet with the right amount of nutrients, and this fact seriously limits the effect that behavior change programs can have. The implications of stunting are so dramatic that we can’t afford to wait until the food systems in LMICs have improved; we can’t wait for these people to be able to afford nutrient-adequate diets. As I said earlier, there is a great need for immediate action. Supplementation and/or fortification with micronutrients have proven to be effective strategies.

How do “plant-based” diets in the Global North differ from “plant-based” diets in the Global South?

Food-Based Strategies to Fight Stunting

Many reports argue that the increase of animal-sourced foods in LMICs is a result of marketing done by the food industry. As mentioned previously, this only partially explains the underlying factors. I conducted studies in Indonesia and Bangladesh that showed that the non-staple food component of food expenditure determines the decrease and increase of micronutrient deficiencies and stunting. In other words, when poor people can afford to buy more non-staple foods, stunting and malnutrition decreases. So clearly, some of the non-staple foods that people buy must be providing essential nutrients (amino-acids and micronutrients).

When poor people can afford to buy non-staple foods, what do they buy, and what guides their purchasing decisions?

One of our tasks is to understand at which moment the marketing of ultra-processed food (such as sugar-sweetened beverages, i.e., soda) is interfering with the natural improvement of the diet of the poor as income increases. Education and social marketing programs promoting healthy foods focusing on young children need to be central to this strategy.

An interesting and promising food-based strategy to prevent stunting in LMICs is the promotion of egg consumption in children 6-23 months of age. One egg a day in a breastfed child of 9 months provides almost all recommended daily nutrients. However, the consumption and availability of eggs remain low in countries with high prevalence of stunting. It is, therefore, important to examine the possibilities of the production of poultry in these countries.

CLF has worked in the past 20 years investigating the unintended negative consequences of factory farms on public health, animal welfare and the environment. We understand with great detail where, how and even why the poultry production industry has made terrible mistakes. We should be able to support LMICs by helping them prevent the many mistakes that are made in poultry production in the US, Europe and Latin America. We have expertise in the policy shifts that can make a difference at the local, state and federal levels, and we can take that to an international level as well. We can also help bolster behavior change campaigns such as Meatless Monday in LMICs, aimed at reaching consumers where they’re most likely to be reached.

But it’s complicated, because while factory farms are not good, the answer is not so simple as free-range chickens living near residential areas, either. Research shows that when children live in households where animals live nearby, the children have a higher prevalence of environmental enteric dysfunction. For example, even though an-egg-a-day can solve the problem of stunting, we would not want to try to solve that problem in a low-income country by giving households chickens to raise in their backyards, only to have children suffering from environmental enteric dysfunction. We mustn’t swap one problem for another.

If animal-sourced foods such as eggs can close the nutrition gap for the malnourished 4.9 billion people in the Global South, how must the Global North proceed in addressing the harms of industrial food animal production?

We must be very careful of unintended negative health consequences when improving the food system. So how do we deal with that? Let’s look again at UNAIDS. The HIV/AIDS community realized that if they really wanted to change, the joint program needed to be inclusive, and the program needed to bridge between many groups—and some of these groups did not agree with, or had ideological objections to the work we were doing. For example, our stakeholders included sex-workers, drug users and gay populations, and certain countries did not (and still do not) accept or tolerate these populations. But these countries remained part of the program, and the discussions and negotiations never stopped. If we hadn’t done it that way, the joint program would have never made so much progress and success. Translating this to food systems work, we must identify which populations may not be welcome at the table, and then we must invite them—and listen to them—despite our discomfort with their presence or ideological disapproval of them.

Whom do we need to invite to the table, despite our discomfort with them or what they stand for?

The EAT-Lancet Commission Paper

In January 2019, the Lancet published the EAT-Lancet commission report (Essential Readings, below), proposing a sustainable diet that operates within planetary boundaries. The commission, consisting of an excellent group of global experts, worked almost three years on the study. The study is a milestone in the field of health, food and climate, but as expected the paper has its limitations. The authors stated that the paper doesn’t provide the strategy or design how this diet can be translated at country or subnational level. For example, the diet proposed by the authors is based on the availability and affordability of food, and agricultural production within the various cultural contexts, as opposed to being based on what would be a nutritionally adequate diet for those varying cultures.

When we use the term “sustainable food system” and “healthy diet,” are we solving the problem of malnutrition that affects 4.9 billion people?

At CLF we are finalizing research that analyzes the climate foodprint of various diets in the context of 139 countries. This analysis will help countries to develop dietary guidelines that can support efforts against undernutrition, as well as efforts against overnutrition, while also operating within planetary boundaries.

There is a great need for improving our food systems against the background of a growing population and climate change. It is, therefore, of utmost importance to work together, and especially important to include and convene those partners with whom we disagree or disapprove. It’s also critical that we move forward despite not yet having all the facts or data that we might like to have. Proceeding this way may make us uncomfortable, but we will have to make the best decisions we can with the information available to us, while continuing to build the body of knowledge. There is no time for ideology or certainty. The urgency of climate change and food systems dysfunction requires us to be inclusive, pragmatic and solution-oriented.

In addressing climate change, how can we be certain to address both obesity in the Global North and undernutrition in the Global South?

Essential Readings

Institute of Medicine and National Academies of Science, A Framework for Assessing Effects of the Food System (2015)

Ruel MT and Alderman H for the Maternal and Child Nutrition Study Group, Nutrition-sensitive interventions and programmes: how can they help to accelerate progress in improving maternal and child nutrition? Lancet. 2013; 382: 536-551

This blogpost builds upon a talk I gave in November, 2018, at the Choose Food Symposium, hosted by the Johns Hopkins Berman Institute of Bioethics.