What Restaurants Can Teach Us about Reducing Food Waste

At the Basque cuisine restaurant Txikito, in Manhattan, beet fronds flavor vinaigrette. The stems from chopped parsley infuse oil. Rabbits are stuffed with their own innards. “We never waste anything,” said Alexandra Raij, who owns Txikito with her husband, Eder Montero. Even cooking water—from chickpeas, from grains—is not wasted. Raij turns these into broth, frequently transporting gallons from one restaurant to another—the couple owns two other Spanish restaurants, La Vara and El Quinto Pino—to avoid menu redundancy. “We serve the chickpeas at La Vara and the chickpea broth at Txikito,” said Raij.

Chefs like Raij have long practiced an art lost to many of us at home: avoiding food waste. Now, as grim statistics confront us with the reality of our wastefulness, restaurants are becoming role models for more responsible consumption. If the growing trend becomes entrenched in our daily lives, the results could have significance far beyond the kitchen.

The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) estimates that 31 percent of harvested food is wasted; that is, not consumed. The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations puts that fraction closer to 40 percent. “That’s probably closer to reality,” said Roni Neff, who teaches environmental health sciences at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. “We have no idea how much is wasted at the farm,” says Neff.

Neff and colleagues at the Johns Hopkins Center for a Livable Future, where she is a program director, recently surveyed consumer awareness and attitudes about wasted food, to provide insights for efforts aimed at reducing such loss in the U.S. The study, published in June in PLOS ONE, part of the Public Library of Science journal collection, found that among the 1,010 survey respondents, concerns about food-borne illness and freshness were the top reasons for throwing away food.

Both of those reasons concern Neff because they don’t reflect reality. “Generally speaking our expiration dates have nothing to do with safety,” said Neff. “They’re really about quality.” Twenty-two percent of survey respondents reported tossing milk after the sell-by date stamped on the carton passed, even though the sell-by date doesn’t necessarily indicate whether it’s safe to drink. “That’s a lot of milk thrown out that never needed to be.”

Sometimes the use-by date on the package is relevant—for meats and dairy in particular, notes Neff—but many packages carry dates for no discernible reason. “Is your salt going to go bad?” asked Neff, as one such example. Consumers, Neff explained, need to better understand when to heed the date and when to ignore it.

“Wastefulness is a modern idea,” said Raij, who notes that traditional Spanish cooking has always used the whole animal and the whole vegetable. “It’s not on trend, it’s just always been that way.”

As renowned New York chef Dan Kluger explains, professional kitchens must also prevent waste as a matter of good business. “In a restaurant, you’re fighting for every penny,” said Kluger, who, after serving in several famous New York restaurants, is opening his first solo establishment this fall. “If there’s a way to use the stems of Swiss chard, you use them.”

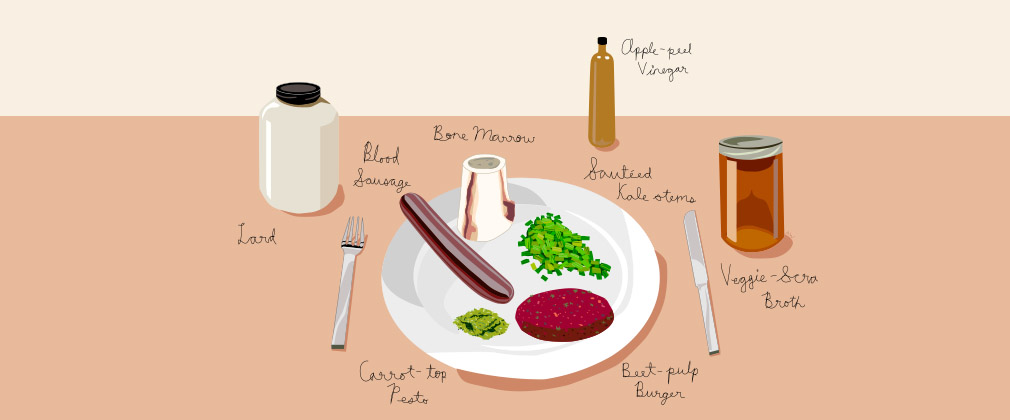

Both Raij and Kluger both participated in WastED, a pop-up restaurant by Dan Barber, the chef and restaurant owner well known for his farm-focused approach to food, dedicated to addressing food waste and reuse. One night, Raij and Montero prepared a Spanish-Asian dish of rich, slippery pork-skin noodles and a dashi made with potato skins and shrimp shells. Kluger’s dish also skewed porcine: crispy pig’s head, accompanied by a carrot romesco using misshapen vegetables, the product of a breeding experiment, which were otherwise destined for the compost heap.

The reduction in waste extended beyond the kitchen. Barber turned pulp from a juice bar into a veggie burger and the spent grains from a brewery into bread. Even the chefs were impressed. “I loved the principle behind using something that’s not really garbage, it’s just not usable in the form that came in,” said Kluger. Raij echoed the sentiment: “I do this in the microcosm of our restaurant every day, but [Barber] went beyond those boundaries.”

Changing practices in the microcosm of our kitchens, though, is a different proposition. “I waste more food at home than I do at the restaurants,” admits Raij. In Neff’s survey, 41 percent of respondents said they didn’t mind wasting food that could be composted. But composted food still wastes the energy needed to harvest, transport and store food. “All that energy didn’t need to be used if you were just going to compost it,” she said.

The Environmental Protection Agency’s food waste hierarchy puts composting at the bottom, after source reduction, feeding people, feeding animals, and industrial use. Raij suggests running our home kitchens like a restaurant, starting with the wise use of our freezers. For example, she suggests making a stock from bones or vegetable ends right away, reducing it into a concentrated “flavor saver,” freezing that reduction in an ice cube tray, and then bagging the cubes for future use.

Smartphones can also help. The Love Food Hate Waste app delivers recipe suggestions for whatever odd assortment of food is in the fridge. PareUp lets users find nearby restaurants with discounted food near closing time. The USDA recently launched Foodkeeper, which provides guidance on food storage to ensure safety and potentially reduce waste.

Larger-scale shifts are also underway. The Consumer Goods Forum, an international group of more than 400 food companies and others involved in retail food and drink sales, pledged to halve their food waste by 2025 at a recent meeting. The Daily Table, a nonprofit, discount store selling excess food donated or sold cheaply by supermarkets and other suppliers that would otherwise have gone to waste, opened in Boston this past June. This fall, United Airlines will fuel a flight from Los Angeles to San Francisco using farm waste and animal fat.

At Johns Hopkins, Neff and colleagues have several ongoing projects. One study aims to identify personal behaviors that predict higher and lower amounts of food waste. The group is also looking at seafood, a food category that is particularly susceptible to waste because of its strong odor.

But as Neff sees it, real change ultimately depends on our willingness to invest in it. “It’s often cheaper to let something to go waste than to actually do something about it.” With enough food wasted to fill the Rose Bowl Stadium each day, such an investment seems well worth our while.