What do food service management companies think consumers care about?

BALTIMORE—Oct.7, 2019. When scanning the dining options in your cafeteria, do you notice any descriptions that are meant to make the food more attractive, such as “cage-free,” “local,” or “sustainable?” I do. With these labels, it’s clear that food service management companies are trying to sell more food by appealing to their customers’ values. But I’ve also taken note of which values the food service management company does not use to market their products—for example, “supports small- and mid-size farms” or “living wage for workforce.” These observations made me curious about which values these companies choose to prioritize, and why.

Some values, such as animal rights, are becoming more easily embedded into food purchases, and formalized with the rise of third-party certifications such as Animal Welfare Approved and American Grassfed. Building on these certifications, the Good Food Purchasing Program (GFPP) created a framework for holistic, values-based food procurement at the institutional level. GFPP encourages purchasers to consider the following values: nutrition, local economies, environmental sustainability, animal rights, and valued workforce.

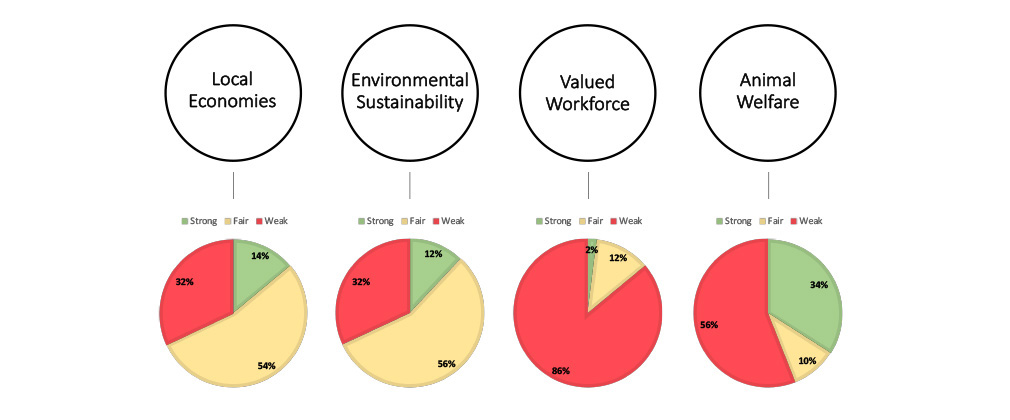

I use this framework in a new CLF white paper, “Beyond Nutrition: A Landscape Analysis of Values-Based Procurement among Food Service Management Companies,” omitting nutrition in order to focus on the four values that extend beyond personal health. Looking only at information that was readily available on company websites, I found that the top 50 food service management companies by revenue had a very different idea about which values should be prioritized in comparison to the GFPP’s idea about which values are important.

For example, some of the companies advertise values such as “local.” But what does “local” mean to them, compared to what it means to GFPP? The Good Food Purchasing Program’s vision for local purchasing is to economically support nearby small and mid-sized farms. But strengthening the local economy was not the main benefit cited by food service management companies with commitments to local purchasing in this analysis. The most cited benefit of local purchasing was “freshness” and “quality,” followed by supporting the local economy and reducing carbon emissions. With this in mind, we can presume that these companies think their customers care more about freshness than they do about strengthening small- and mid-sized farms.

Some companies appeal to customers on the basis of “food miles,” but focusing on “food miles” provides an incomplete picture of a food’s carbon footprint, and research shows that the type of food and its method of production have a greater impact than how far the food has traveled. So why are companies using this as a selling point? Do they lack this fuller understanding of all of the ways food produces greenhouse gases over its lifecycle? Or are they trying to simplify the issue because they believe a simpler understanding will resonate more and sell more products?

These questions are worth puzzling over for their implications for future marketing and policy. Unlike the “USDA Organic” certification, which has an official definition using standards set by the government, “local” is currently an unregulated term, and food service management companies are setting their own standards for the distance between where the produce was harvested and where it was served that is designated “local.” This leaves companies more flexibility in how this term can be used in their marketing, with less oversight to protect consumers from misleading claims. Formalizing a definition or a certification label can help consumers make informed food choices that align with their values.

For more recommendations for food service management companies and consumers, read the latest CLF white paper: “Beyond Nutrition: A Landscape Analysis of Values-Based Procurement among Food Service Management Companies.”

Hannah Louie is a 2019 Research Contractor at the Johns Hopkins Center for a Livable Future, and graduate of the Master of Public Health program at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health with a concentration in food systems and a certificate in public health advocacy.