How the Food Sovereignty Movement Is Reflected in USDA Data

BALTIMORE—Feb. 20, 2020. This post is the seventh in a series—Connecting Agriculture Policy to Your Health—by Johns Hopkins DrPH student Lacey Gaechter and special guest contributor Melvin Leroy Arthur, MS.

Introduction—Lacey

Does the USDA’s Census of Agriculture reflect broader food sovereignty and resilience movements happening within the United States? In my last post, I described some distinctions between the terms “agriculture” and “food production.” In this post, I explore how food sovereignty and resilience movements are reflected in agricultural production trends for farmers of color.

To help me, I’m very honored to be joined on this post by my friend, colleague, and personal hero Melvin Leroy Arthur. Mel is an expert on Northern Arapaho foodways, a research scientist at the University of Wyoming, and the author of a recent article, published in the Journal of Agriculture, Food Systems, and Community Development’s issue on Indigenous Food Sovereignty in North America. He’s also a member of the Hinono’eiteen nation, also known as the Northern Arapaho tribe. Below, Mel provides a valuable perspective on part of the background that influences how some of us who have worked and lived in communities fighting for food sovereignty interpret data from the USDA’s Census of Agriculture.

Mel chose to contribute his expertise to this post through the lens of his work on Growing Resilience. Growing Resilience is an action and research project that brings home vegetable gardens to people living on the Wind River Indian Reservation in Wyoming, then works with these communities to measure the gardens’ impacts. With acknowledgement that home gardens are distinct, in many regards, from the farms tracked in the United States Census of Agriculture, Mel’s expertise and the insights he shares here speak to larger, cultural motivations for growing food.

Growing food on the Wind River Reservation—Melvin Leroy Arthur

My experience with food producers from my original home on the Wind River Indian Reservation spans close to 10 years. My work and personal experience has shown me that Northern Arapaho and Eastern Shoshone tribal members relate their own personal gardening experience directly to health, and others have placed the importance of generational knowledge as a key factor when getting their kids involved.

Tribal members who garden for health are usually motivated by the deteriorating health of a close family member who might be losing limbs to diabetes, or a child who has already been diagnosed with the disease at a young age. Community members have been desensitized to trauma, which makes realizations pertaining to their own health status, and that of their children and grandchildren, feel more desperate. As an oppressed, Indigenous community we have not found ways to heal ourselves under the Whiteman’s health paradigm. As a result, when a better option comes along, we adopt it, especially if it makes our lives easier. Gardening gives tribal members an opportunity to put importance on eating healthy foods and creating a healthy foodway. Today, this makes life easier for us because we feel like we are improving our own community health.

Home gardening also gives tribal members opportunities to make their own connections to past generations including those of family and community. There is a long tradition of home gardening in the community that dates back to the introduction of the Arapaho people to the Wind River (for more information on historic Arapaho foodways, see my recent publication on the topic here). At that time our head men built home gardens as soon as they were imprisoned on the reservation, and this custom was further promoted through policy and World War II Victory Gardens. Self-sustainability was required for the Northern Arapaho people to survive because if they didn’t they would not eat, despite promises made by the Whiteman to provide food for Indigenous people who agreed to settle on reservation lands. Northern Arapaho tribal members were expected to become farmers when they were imprisoned at the Wind River Indian Reservation. Policies and funds were available for this to become a reality, but all the officials of this time and place took the government payments and built an agriculture system for the people north of the Big Wind River, which are the white people. This left nothing for the Northern Arapaho people, and as a result they had no funding to build large scale agriculture.

Most of today’s tribal food producers have been robbed of this history and they can only relate to a time when our grandparents all had gardens, and we remember what was produced as a result of the home gardens we seen as young people. I have heard tribal producers speak of the home-gardens they seen as children when they could just go out to the garden and get something to eat when they got hungry, or how they never went to the grocery stores in town when they were growing up. Through the Growing Resilience project tribal members have reconnected to the collective memory of generations past. They want to pass that down to their children, no matter how it looks or what is grown; they just want to get outside and experience it for themselves.

Ag Census Data—Lacey

In my last post about some of the differences between agriculture and food production specifically, I noted that most corn and soybeans – our nation’s two largest crops – are not raised to feed people but instead are used for ethanol and livestock feed. Of course, agricultural acreage dedicated to raising flowers, tobacco, dogs, cats, animals for fur coats, and thoroughbred horses also does not contribute to our food supply for human consumption.

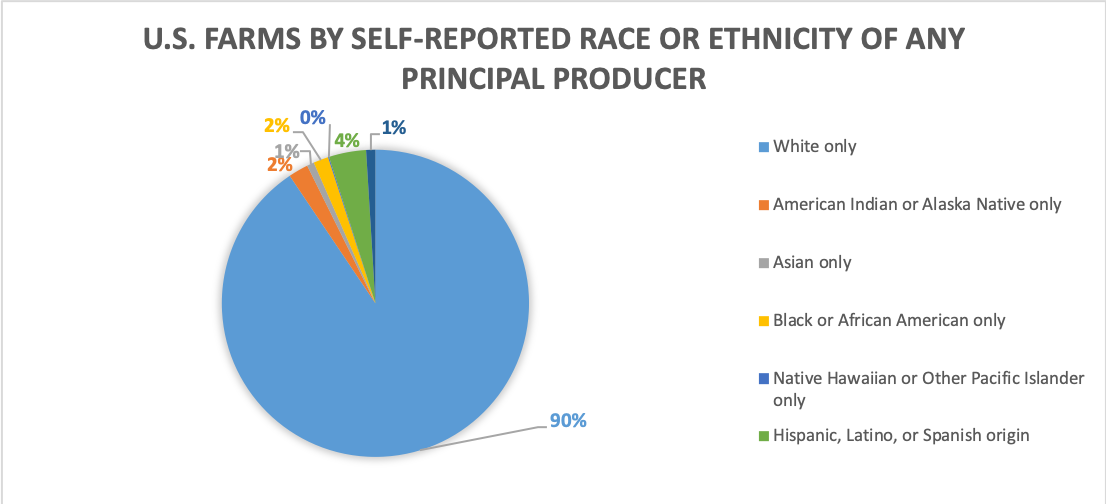

Examining the difference between agriculture and food production got me wondering about who grows what in the United States. One answer is that all farm types in the United States are predominantly run by white people (see Figure 1).

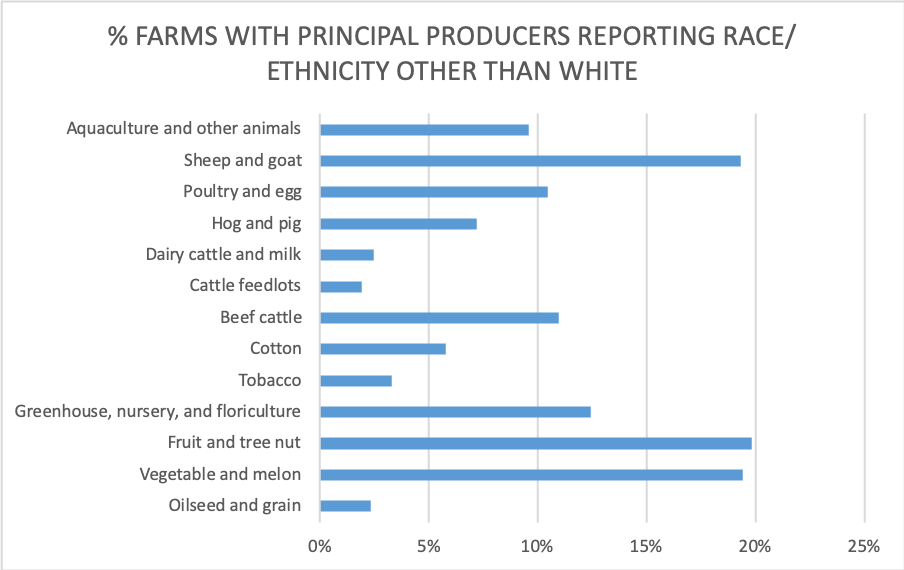

Within that context, however, it is noteworthy that the three agricultural sectors with the highest percentage of farms run by people of color are sectors that very directly produce food: Fruits and Tree Nuts, Vegetables and Melons, and Sheep and Goats (see Figure 2). In fact, a farm run by a person of color has 1.4 to 6 times the odds of growing vegetables and/ or melons than farms run by white people. The gardens that Mel helped people on the Wind River Indian Reservation grow are too small to be captured in the above census data. Thus, small per capita efforts like those of Growing Resilience and other community food sovereignty work do not even contribute to the trends that appear in USDA Census of Agriculture data.

Meaning Behind the Data?—Lacey

There are admittedly many reasons that the numbers pan out this way. For example, people of color have been systematically denied resources like land and investment capital that are needed to run large operations, including grain and oilseed farms. As Mel notes, “In relation to the numbers from the Census of Agriculture, we on the reservation would be the outliers hinging on the fringes of funding, but we have created an infrastructure that will hopefully carry the work on for future generations.” People of color also often have to reconcile histories and current realities in which agriculture was/is used as a tool of oppression against them.

Furthermore, farmers who both do and do not identify as white undoubtedly participate in agriculture for a variety of reasons. At the same time, people of color have identified growing their own food as a form of protest against a history of colonialism and oppression by improving their own and their community’s health, achieving community food sovereignty, and reemphasizing traditional foods.

Access to healthy foods and the lands where those foods are produced are also concepts long intertwined with movements of sovereignty and against oppression. This connection in the African American community is well outlined in the 2018 book by Monica M. White, Freedom Farmers: Agricultural Resistance and the Black Freedom Movement. White begins her exploration by highlighting the importance of slave gardens to not only the survival of first-generation enslaved Africans brought to the “New World,” but also to their resistance of cultural genocide. She then follows the centrality of food and land for food production in the famous efforts of Booker T. Washington, George Washington Carver, W.E.B. Du Bois, Martin Luther King Junior, Fannie Lou Hamer, and Malcolm X and the Black Power movement.

Similar histories of resistance to oppression through healthy food cultivation have played out in most communities of color in the United States. This is true of people of Asian and Latinx descent – whose labor has been and is disproportionately exploited to produce the foods that fill the shelves of grocery stores they often cannot themselves access. It is also certainly true of American Indian communities as described above in this post and in scientific literature, especially recently in the Journal of Agriculture, Food Systems, and Community Development’s issue on Indigenous Food Sovereignty in North America.

Thus it may be the case that the numbers in our most recent Census of Agriculture speak to a larger truth about underlying trends in motivations for farming. Perhaps this interest is even statistically stronger among farmers of color than among white farmers. As both scientists and advocates, it is meaningful for Mel and me to see our lived experiences and expertise in social sciences reflected in the hard numbers collected in our country’s Census of Agriculture.

For a more in-depth discussion and references, find the PDF version of this story here.