Food Security in the Time of Covid: It’s Not Charity, It’s Justice

BALTIMORE—March 30, 2020. Food policy councils across the nation are scrambling to meet the needs created by the coronavirus pandemic in their communities, and several common themes are emerging across all states and regions. The pandemic is new to us, but the needs are not— the virus is drawing our attention to long-existing problems in our food systems, and exacerbating them. Food insecurity is not a new problem, but the virus is increasing the demands on food banks across the country, and it’s reminded us that millions of children rely on school to provide at least one, if not two or up to three meals a day. The virus is also reminding us that many farmers live on the margins, that we rely on farmworkers with precarious immigration status, and that the industries around food distribution and retail are dependent on front-line food service workers who cannot afford to be unemployed for even a short period of time.

In addition to the long-standing food system challenges, novel food system problems have bubbled to the surface. Before a recent federal ruling, some states, but not others, had declared farmers markets essential businesses that can remain in operation during shelter in place orders, a decision that affects not only consumers, but also producers who rely on the markets for revenue. Visa interviews for migrant farmworkers have ceased, a decision that not only affects the farmworkers themselves, but also the farmers and restaurants who rely on them as employees. Many are concerned about price gouging across the country, and some restaurants have suddenly found themselves with extra food on hand that isn’t being used and in need of recovery. And, of course, millions of people in food service, including those in casinos, have suddenly lost their income.

Last week, the Johns Hopkins Center for a Livable Future’s Food Policy Networks project convened more than 200 members of food policy councils for a roundtable discussion of how they’re meeting their communities’ needs during the Covid-19 crisis. The online roundtable featured speakers from councils in Colorado, Iowa, Maryland, Mississippi, Pennsylvania, and Rhode Island, as well as questions and recommendations from the 200+ participants.

The speakers shared solutions and resources, as well as important framing for how to address the problems that have become so stark in the last few weeks. Through the roundtable, participants learned about a bike food delivery program in Dubuque, Iowa, and how they’re shifting from community drop-off points to door-to-door delivery. We learned of challenges faced by the suddenly unemployed workers in the casino industry in the Gulf Coast, and we learned of efforts in Rhode Island to have food service workers recognized as first-tier emergency responders in the hope of getting them better access to testing. Hits to the aquaculture and seafood industries were discussed, as well as how all these problems are affecting immigrant populations especially hard, as so many of them are food-insecure even during “normal” times. Michaela Freiburger of the Dubuque County Food Policy Council mentioned that many of those in need of emergency food could also be farmers themselves, because the food they grow is typically for livestock, not for human consumption.

In the wake of this pandemic, we’re seeing in stark relief pre-existing food systems problems, and so many solutions. But there is also a strong common thread that has emerged: we need to see these solutions as justice, not charity. Dawn Plummer of the Pittsburgh Food Policy Council, said, “We are really in a moment of push around charity. We need to make sure that we activate our charitable food and emergency food networks. But the justice side is important as well. So, [that means] making sure that we have those communities that are most vulnerable at the center [of policies being proposed]. For us, that’s frontline food service workers, that’s farmers, that’s small business owners, restaurant owners.”

Plummer mentioned a common theme: that while local officials are grateful for the work of nonprofits to meet food needs, we can’t simply rely on nonprofits to feed food-insecure people. There must be legislation to address the needs for the long-term. “These are policy needs,” she said.

Speaking about the needs in Mississippi, the poorest and second-most food-insecure state in the union, Noel Didla of the Mississippi Food Justice Collaborative talked about what is true in this country at all times, whether we’re in a pandemic or not: “Repressive, anti-black, anti-indigenous, anti-brown, and anti-poor policies continue to govern us,” she said.

She called upon participants to always keep in mind the need for policies to be people-centered, driven by and grounded in ethics and public health. “We need human rights-centered, racially equitable, environmentally just, economically equitable, public health-centered, labor rights-driven, and food sovereignty-centered [policies] to transform food systems across the state,” she said.

Plummer’s and Didla’s sentiments were echoed throughout the roundtable by all speakers as they shared creative solutions, such as a Rhode Island food hub that was serving institutions and restaurants now pivoting to do home delivery of local food products. Nessa Richman of the Rhode Island Food Policy Council shared another example of a large farmer distributor who is going to have empty refrigerator space due to the changes in the market and loss of restaurant sales and institutional sales—that distributor is now offering the refrigerated space to emergency food providers. But intertwined with sharing of resources and solutions was the agreement that even though what’s needed in the moment may seem like emergency measures, those needs are ever present.

As Plummer said, “I think we’re well positioned as a food movement to come in with the vision that we’ve been developing in our communities for a long time, and now it gets real.”

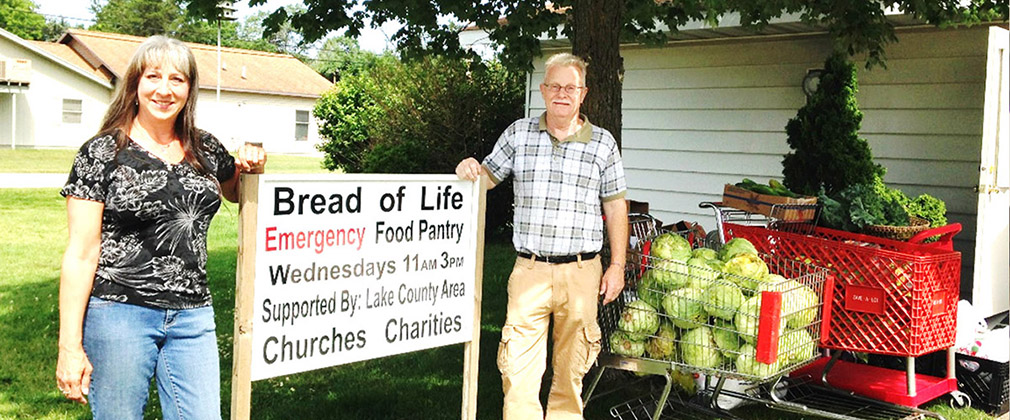

Image: Bread of Life Food Pantry, Baldwin, Michigan, by Kendra Gibson, CLF Food Policy Networks Photo Contest, 2018.