China’s Changing Diet: Meat and Dairy on the Rise

Reflections on China’s Changing Diet: Local impacts, global implications, and promising solutions.

China is eating differently, and it matters—a lot! China’s sheer size and growth mean that even small changes in diet and lifestyle patterns have large impacts in terms of public health, food safety and the environment. In this first blogpost, we summarize how and to what degree China’s diet has actually changed. Our second post will discuss the local and global implications of the shifts in China—and how China’s health experts are encouraging citizens to adjust their food and lifestyle choices. Finally, we will suggest simple and effective actions such as Meatless Monday that can be leveraged individually and collectively to move the dial toward a healthier China and thriving world.

China is eating differently, and it matters—a lot! China’s sheer size and growth mean that even small changes in diet and lifestyle patterns have large impacts in terms of public health, food safety and the environment. In this first blogpost, we summarize how and to what degree China’s diet has actually changed. Our second post will discuss the local and global implications of the shifts in China—and how China’s health experts are encouraging citizens to adjust their food and lifestyle choices. Finally, we will suggest simple and effective actions such as Meatless Monday that can be leveraged individually and collectively to move the dial toward a healthier China and thriving world.

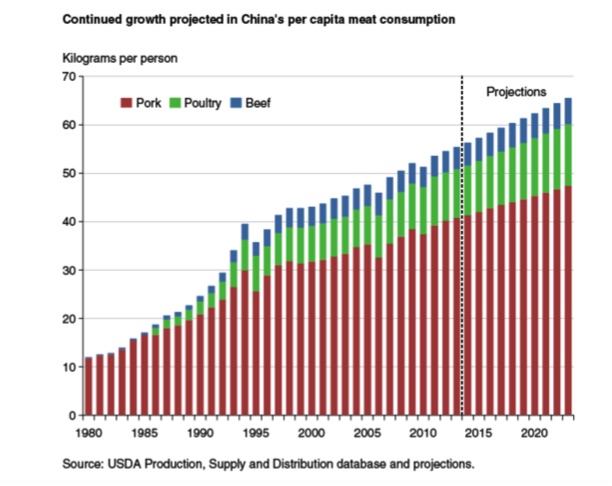

China’s nutrition transition has been and continues to be rapid and substantial, particularly in regard to its consumption of animal products. Through the late 1980s, families relied on local resources to produce food—rural, household pork operations that relied on forages and food waste for feed. Since then, the shift to specialized farm enterprises and commercial feed mills has been fueling the economy and is being fueled by the economy. Farm labor wages increased, and more problems with animal diseases increased pressure to move farming to large commercial operations. Urbanization and improved living standards have also played a big role, with 63% of the population predicted to be living in urban areas by 2023. Rising incomes support the growing purchase and value of meat.[1]

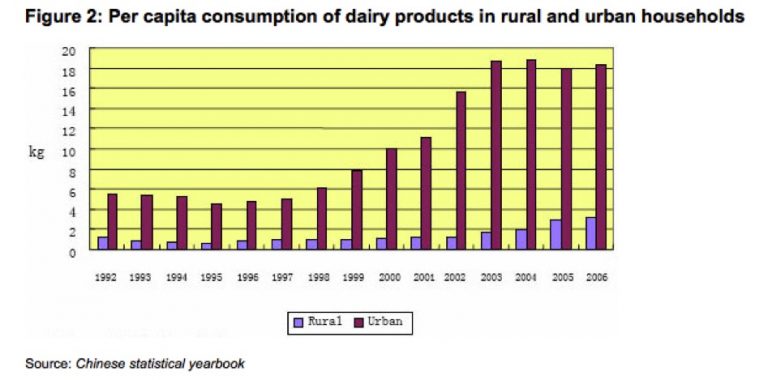

China’s dairy consumption trend also cannot be ignored. In the past, dairy products were a very negligible part of the Chinese diet. With the shift toward Western diets, people are now consuming remarkably greater amounts of milk, yogurts, and ice cream—and even cheese at fast food restaurants (cheeseburgers!). The difference in dairy consumption between urban and rural is stark, but as urbanization continues, the amount of dairy consumed will also rise.[2]

China’s dairy consumption trend also cannot be ignored. In the past, dairy products were a very negligible part of the Chinese diet. With the shift toward Western diets, people are now consuming remarkably greater amounts of milk, yogurts, and ice cream—and even cheese at fast food restaurants (cheeseburgers!). The difference in dairy consumption between urban and rural is stark, but as urbanization continues, the amount of dairy consumed will also rise.[2]

Diet changes in China are felt all around the world environmentally and economically. China now feeds 20% of the world’s population and consumes half of the world’s pork. Raising more hogs, far and away the livestock of choice in China, means producing more feed domestically and importing feed from other countries—both activities have a significant carbon footprint.[3] In addition to pork, intake of eggs, poultry and dairy products continues to grow. Interestingly, the Chinese Dietary Guidelines call for 300 grams of milk and dairy per day, which is more than 10 times what the average Chinese citizen consumed in 2007. If the Chinese come close to meeting the guidelines for dairy intake, their consumption of dairy alone would have a significant negative impact on GHG emissions, water, pollution and the environment as well as the population’s health.

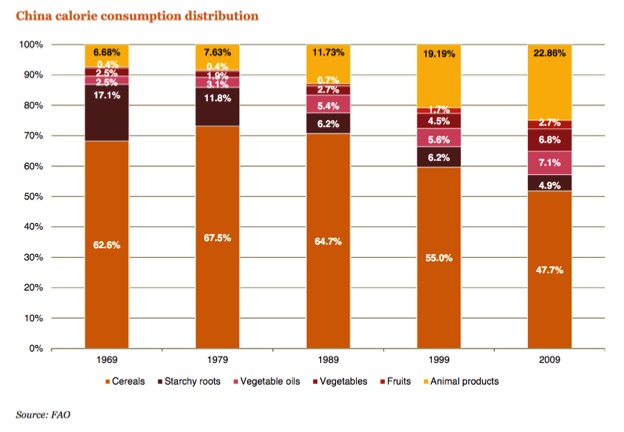

Meat and dairy consumption follow earlier changes that are also key indicators of the Chinese nutrition transition, including more sugars, oils and refined grains. Since 1989, sugar intake has increased 40-fold from 1-2 grams per day to 40 grams per day in 2011.[4] Cheaper oils fueled a shift in cooking methods toward frying over traditional steaming or boiling. More processed grains are being consumed in place of legumes and courser, whole grains.[5] Salt is at 10.5 grams per day, on average per person, which is nearly 3 times as much as in the U.S. Overall calories have nearly doubled from an average of 1,800 calories per day to over 3,000 calories per day in 2011 (FAO). And with economic growth, trends continue toward eating away from the home and reliance on convenience and processed foods.

Meat and dairy consumption follow earlier changes that are also key indicators of the Chinese nutrition transition, including more sugars, oils and refined grains. Since 1989, sugar intake has increased 40-fold from 1-2 grams per day to 40 grams per day in 2011.[4] Cheaper oils fueled a shift in cooking methods toward frying over traditional steaming or boiling. More processed grains are being consumed in place of legumes and courser, whole grains.[5] Salt is at 10.5 grams per day, on average per person, which is nearly 3 times as much as in the U.S. Overall calories have nearly doubled from an average of 1,800 calories per day to over 3,000 calories per day in 2011 (FAO). And with economic growth, trends continue toward eating away from the home and reliance on convenience and processed foods.

Food-based Dietary Guidelines (FBDG) are sets of recommendations or guidance provided by governments on how citizens can choose foods for health and well-being. They are tools that can be used to promote healthy diets and often serve as the basis for developing food and agriculture policies. A handful of countries have also used their FBDGs to address sustainability.

Like the U.S. dietary guidelines, China’s newest 2016 Dietary Guidelines focus primarily achieving on health objectives; however, they also have the potential to make a positive environmental impact if they were to result in a reduction in meat and animal products consumption. But it’s complicated!

More about the implications of the Chinese diet, the new Dietary Guidelines and how Meatless Monday can be a part of the process in Part 2 and 3.

[1] Hanson J, Gale F; China in the Next Decade: Rising Meat Demand and Growing Imports of Feed; USDA Economic Research Service, April 7, 2014

[2] China: Dairy product quality as the new industry driver; FAO; accessed 7-29-16; http://www.fao.org/docrep/011/i0588e/I0588E04.htm

[3] China’s agricultural: Roads to be travelled, Price Waterhouse Cooper; October 2015 http://pwc.blogs.com/files/chinas-agricultural-challenges-6-oct_final.pdf

[4] Sugar in China: ISIC 1542; Euromonitor. Euromonitor International. 2013.

[5] Popkin et al, The nutrition transition in China: a cross-sectional analysis.; Eur J Clin Nutr. 1993 May; 47(5):333-46.