Wendell Berry: This Is Still a Very Beautiful World

December 8, 2016

Video | Blogpost | | Essay Reading by Wendell Berry

Video | Blogpost | | Essay Reading by Wendell Berry

“I can’t give anybody hope,” said Wendell Berry, the award-winning author, poet and farmer from Port Royal, Kentucky. “Hope has to come up out of you … To find something worth hoping for is a very good place to start. There are things worth hoping for, there are good people, this is still a very beautiful world.”

Mr. Berry, who champions the agrarian way of life and what he describes as decent, loving kindness, was responding to a question about how to proceed in this era percolating while the new President-elect builds his administration. Mr. Berry is an outspoken critic of materialism, consumerism and what he calls the “world-ending fire” created by the Industrial Revolution and corporatism. “Well, I’m still on the losing side,” he said. “I’ve taken up my residence on the losing side, and I’m not gonna live a day on the winning side.”

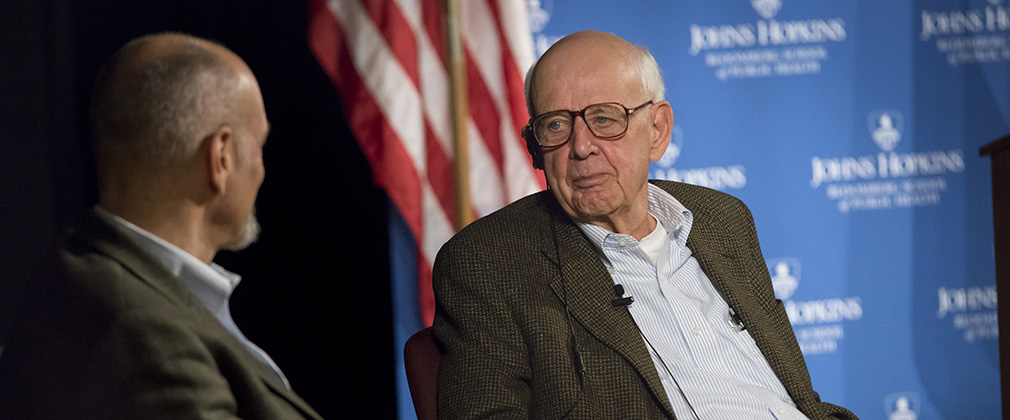

Yesterday Mr. Berry, in a public conversation with journalist Eric Schlosser, addressed a filled-to-capacity room at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health in celebration of the Johns Hopkins Center for a Livable Future’s 20th anniversary, an event arranged by CLF policy director Bob Martin. He spoke about his influences as a writer, his influences as a spiritual person, his connection to Kentucky, the land and more.

He began the conversation with Schlosser by talking about a term he’s coined—industrial fundamentalism. As he described it, industrial fundamentalism is a kind of faith among people that industry can do whatever needs to be done by its own standards. If industry doesn’t know how to do what needs to be done, it will learn quickly, because science is “coming right along.”

He told a story about dairy farmers who have been so industrialized in their operations that they go to the grocery store and buy milk in cartons. For Mr. Berry, this story represents so much of what’s gone wrong with our culture. Bureaucracy is one of the thieves of our happiness, he suggests, by replacing the honesty that comes from knowing and loving your neighbors with quality control measures that don’t work and wear us down. People are separated from their land, and this, he contends, is one of the greatest harms done to us. “The first time I ever saw strip mining,” he said, “I thought it was shocking, unspeakable. It never occurred to me that people could do a thing like that.”

He rued how today’s economy has destroyed our own self-reliance. “We depend on suppliers for everything we have,” he said. The American farmer who grows corn or soybeans is an example of this total dependence; the farmer’s economy consists only of buying and selling. “The farmer has nothing to fall back on, nothing that he can do for himself,” he said. “There’s very little that the farmer is taking from nature.” This is in sharp contrast to an older model of farming, in which farmers could always fall back on subsistence—land under their feet that they could use—and an attitude recalled by Mr. Berry from farmers in his childhood who also kept gardens: “They may run me out, but they’ll never starve me out.”

On climate change, he said that while he acknowledges it, he finds it to be a distraction. By focusing on climate change, he said, we turn our focus away from the multitude of things that are wrong. “We need a broad-fronted economic movement to protect everything that’s worth protecting, to stop damage to everything that’s worth keeping,” he said, suggesting that such a movement would need to become part of every day life for everyone. “A whole program like that needs to be carried out by whole people who are not ashamed to use words like love, honesty and fidelity.” He also suggested that the reason we’re not seeing enough traction on climate change is that we are using the wrong tactics to make people care—fear, guilt and anger. Instead of basing our entire strategy on how scared we are about the future, we should base a strategy on love. “We all need to find things we love to do, and do them,” he said.

“We’ve been talked out of love, mercy, kindness,” he said, laying some blame at the feet of scientists who strive to reduce or quantify such qualities. “We’ve got to take those things back.”

—Christine Grillo