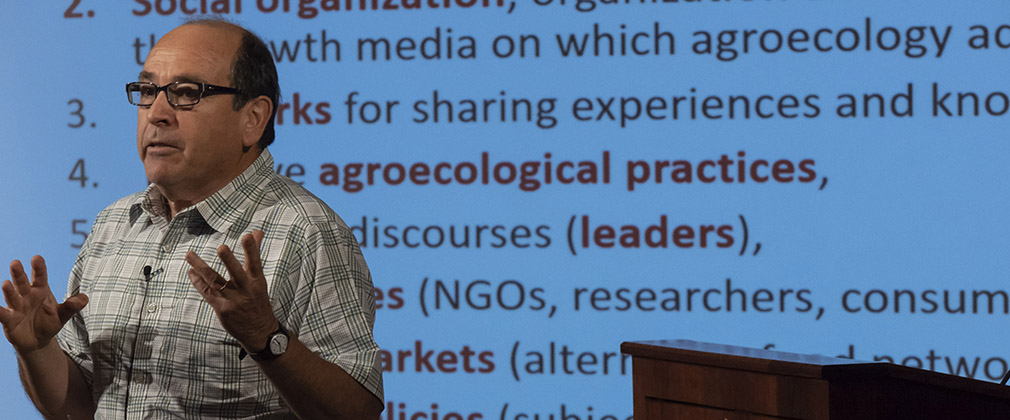

Lecture by Miguel Altieri

18th Annual Edward & Nancy Dodge Lecture

September 21, 2018

Transform or Reform?

When talking about how to address looming problems in the current global food system, Miguel Altieri, PhD, likes to quote Albert Einstein: “We can’t solve problems by using the same kind of thinking we used when we created them.”

Altieri was speaking at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health as the honored guest of the Johns Hopkins Center for a Livable Future’s 18th annual Edward and Nancy Dodge Lecture, with Edward Dodge’s son, Randall Dodge, in attendance. The lecture was hosted with the Center by the Department of Environmental Health and Engineering.

Altieri, who spent the past 37 years at the University of California, Berkeley, as professor of agroecology (now professor emeritus), shared his ideas about what he believes should be our alternative agricultural system: an agroecology based on centuries-old socioecological and cultural systems used by indigenous and peasant communities. He referred to the “campesino a campesino” movement as a methodology to use as a model for distributing knowledge and called for a “re-peasantization” of food systems.

He cited several studies showing that acre-for-acre, small farms owned and operated by peasants—using time-tested techniques such as intercropping, crop rotation and polycultures—have higher levels of output than “conventional” or industrial farms. He also showed higher levels of resistance to climate change-related weather events such as hurricanes among farms developed with agroecological models.

“We must move peasants to autonomy and out of debt,” he said, “and recover and restore territories from agribusiness.”

A key point of his vision is a system of what Altieri describes as “agroecological lighthouses,” or hubs where farmers come together and work collaboratively; sometimes scientists would also come to learn. For farmer-to-farmer networks to grow in strength, though, consumers would need to act in solidarity and push collectively, as part of a social movement, for a complete overhaul of the food system to bypass the corporate control that currently determines food production and consumption in the United States.

Altieri made a point of distinguishing between the agroecology that is currently fashionable and the agroecology that he has been espousing during his career at Berkeley. His vision paints agroecology as the guiding principle in a transformation of the food system, whereas newer models designate agroecology as part of a toolkit (with other tools such as biotechnology, modeling, meta-analysis and other innovations) geared toward reform. Transformation or reformation? Altieri is very clear about his preference: transformation. (Last year, FAO Director-General José Graziano da Silva called for a transformation and referred to agroecology as the main driver of that; he also said, “Addressing the diverse challenges of the 21st century will require a combination of responses.”)

But he acknowledges that a new paradigm requires new ethics for our country. “We must realize the right to food,” he said. “We need to challenge the right to private property.”

How does he suggest that Americans might mobilize to transform the food system?

“If you leave it to market forces, it’s not going to happen,” he said.

The drivers will be crisis, social organization, networks of knowledge and a lot of discourse.

“Alliances should be led by the people, not scientists,” he said.

—Christine Grillo

The Edward and Nancy Dodge Lecture is supported through the R. Edward Dodge, Jr. and Nancy L. Dodge Family Foundation Endowment, established through the generosity of Dr. Edward Dodge, MPH ’67, and his late wife Nancy to provide core funding for the Center for a Livable Future.