Wartime Rationing, Food Supply and Meatless Campaigns

Today is World Food Day, a day of action dedicated to achieving Zero Hunger worldwide. So it seems especially appropriate today to consider the predictions concerning the rising population, which may reach 11.2 billion by 2100. A common concern associated with more people on the planet is food production and access. How will we produce enough food to feed a growing population? And how do we do this sustainably? One potential solution lies in what we do with the food we produce: we currently waste about one third of the food we produce for human consumption annually.

For some new solutions we can look back to the old, particularly the food conservation efforts of the First and Second World Wars, when massive food redistribution programs sought to reduce American at-home food consumption and channel more food overseas to Allied soldiers and Europeans. During the First World War, the amount of food consumed in the United States between 1918 and 1919 was reduced by 15% due to the wartime food conservation efforts.

On September 18, 1917, a Wisconsin state politician named Magnus Swenson suggested Meatless Tuesdays to decrease meat consumption in the state. Just five weeks later, on October 30, 1917, Food Administration Director Herbert Hoover announced nationwide meatless days, which asked Americans to skip pork and beef one day each week. In New York City, hoteliers and restaurant managers rose to the challenge and saved 193,545 pounds of meat on a November meatless Tuesday. Similar effort in wheat conservation enabled the government to save precious wheat and beef for the troops.

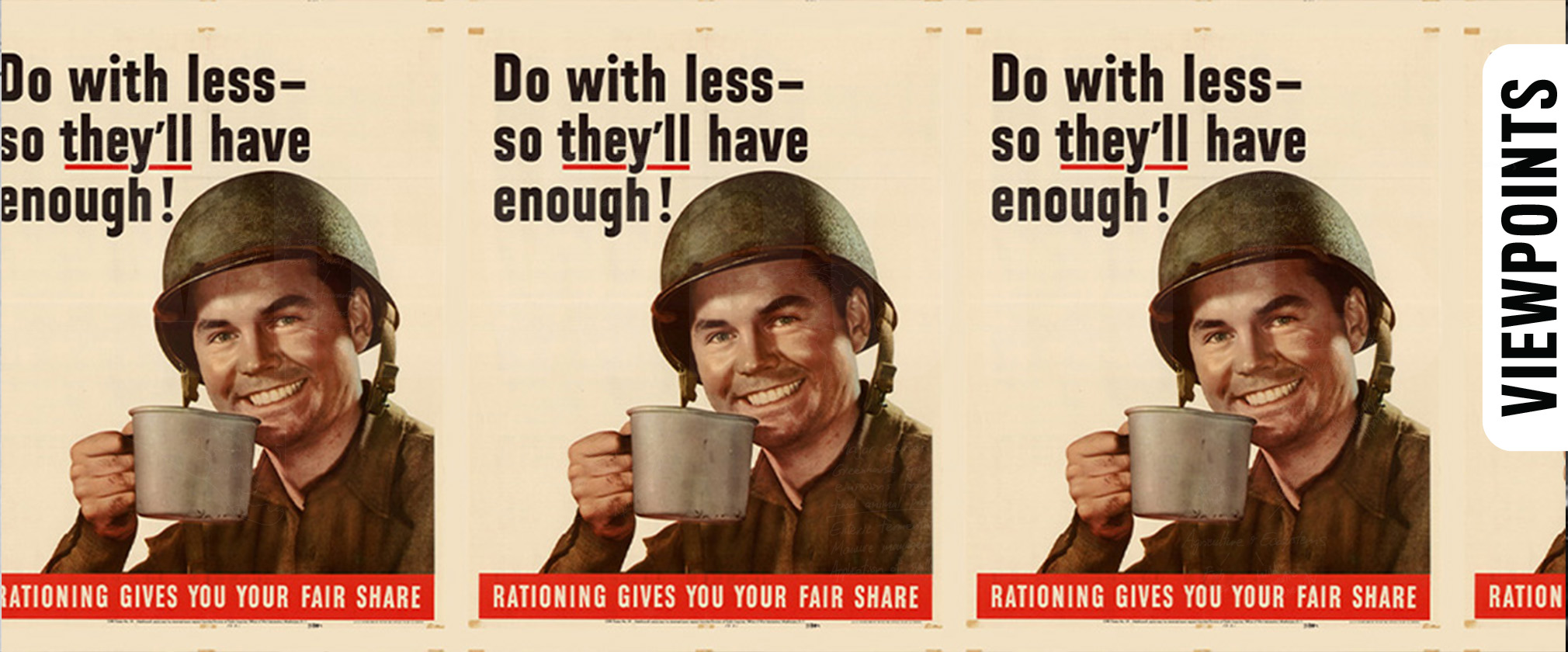

In World War II, the introduction of rationing in American society saved food for the troops and improved food access among lower income Americans. While many goods were still in scarce supply, many poorer people were able to access items like meat and sugar, which that they would have been unable to afford due to rising prices caused by increased demand and low supply. Even the wealthy could not purchase more of rationed items than they were allotted, preventing a concentration of items in the hands of those who could afford to the pay the most for them. Ration booklets allotted all families access to certain amounts of fats, meats, sugars and other dietary requirements and set the prices for these foods. A rationing system aimed to ensure that all Americans, regardless of economic status, were able to access the same amount of coffee, meat, sugar, and fat. Rationing kept wartime prices of scarce commodities at affordable prices while also limiting the amount each family could purchase.

During the World Wars effortsto reduce at home consumption and to ensure that wartime shortages affected all Americans equally can give insight into modern methods for adjusting food consumption and distribution to ensure a fairer, better fed tomorrow. In fact, some modern campaigns against food waste harken back to World War-era campaigns. One such campaign is called “I Love Leftovers.” Like the World War I-era campaign for food saving that encouraged housewives to use their leftovers to the fullest in order to save food for the troops, this campaign utilizes the most modern media of the time as well as cooking lessons, suggestions, and recipes to reduce food waste. Another modern campaign, Meatless Monday, takes its inspiration from World War I’s meatless day campaigns and asks people to reduce meat consumption by not eating meat one day each week.

There are lessons to be learned from history. The Meatless Tuesdays of World War I were ultimately not successful in reducing overall meat. This was due mainly to the rising wartime wages that enabled many lower income people to purchase meat regularly for the first time. The government was still successful at getting enough meat, wheat, and other staples to home front due to increased, technologically-aided production during the time period. In World War II, efforts were more successful at reducing meat consumption. In contrast to World War I, World War II paired governmental restrictions through the Office of Price Administration in the form of rationing with moving media campaigns about saving for the troops, whereas the earlier campaign was completely voluntary. At the same time, however, the World War I campaign was extremely successful at spreading its message all across the nation, and during a time when mass media and the Internet did not exist! Perhaps a lesson learned is that the redistribution policies of the future may be more effective when they incorporate policy with media campaigns in order to effect change.

With a growing population and pressure from climate change threatening our livelihoods, we need to think critically about how our food is produced, distributed, and consumed. Some of that unequal food distribution can be remedied using campaigns that look to earlier food redistribution campaigns in America during the World Wars. From the campaigns of the World Wars, we can learn the importance of eating locally, reducing waste, and eating foods that require fewer resources to produce.

Victoria Brown is a senior at Sarah Lawrence College studying economic history, food policy, and public health. In her spare time she enjoys reading, writing, traveling, and making art.

Image: United States. Office of War Information. Division of Public Inquiries. 1943.